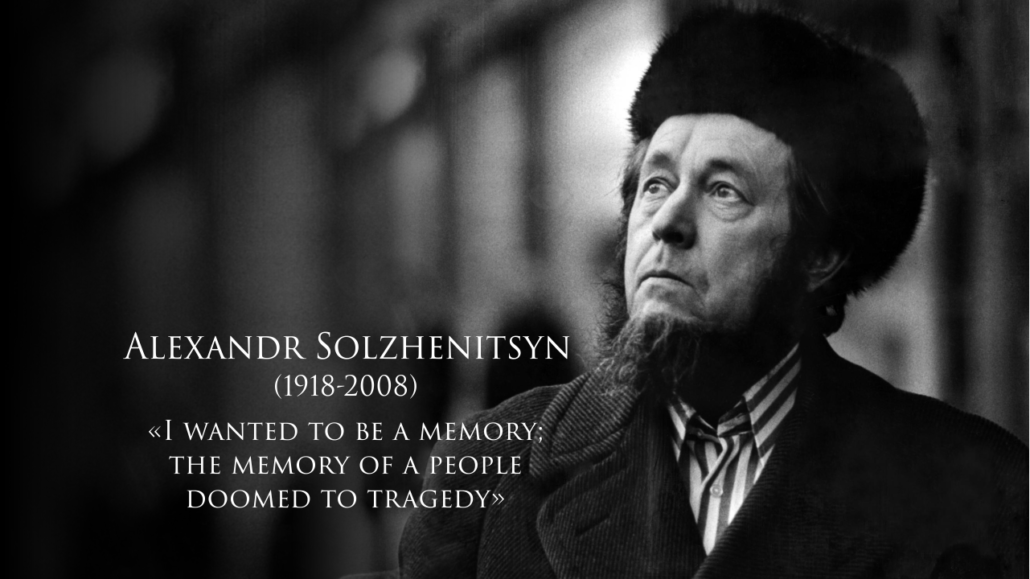

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008)

“I wanted to be a memory; the memory of a people doomed to tragedy”.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian novelist, historian, and outspoken critic of both Soviet communism and Western liberalism, is a powerful example of a writer who beautifully incarnated in his life the two specific virtues of leaders, which are magnanimity and humility.

Solzhenitsyn was magnanimous. He possessed a high sense of his own dignity at a time when the Soviet totalitarian state trampled on dignity to a degree never seen before.

Solzhenitsyn’s mission could be summarized in a few words. He said: “I wanted to be a memory; the memory of a people doomed to tragedy”. Solzhenitsyn wanted to become the powerful and universal voice of the millions who had perished under communism. “I will publish everything!”, he said. “Tell all I knew! … for those who had been stifled, shot, starved or frozen to death.”

Solzhenitsyn understood he had to cry out the truth “until the calf breaks its neck butting the oak, or until the oak cracks and comes crashing down. An unlikely happening, but one in which I am very ready to believe.”

A writer who set to himself such an exalted goal – in such a time and in such a place – this was for the whole of humanity and for Russia in particular a sign of a formidable hope. The Russian poet Olga Sedakova, who read Solzhenitsyn in samizdat, witnesses: “This new knowledge of the scope of the evil called forth by Communism, which could get a man killed if he were not prepared, hardly exhausted Solzhenitsyn’s writings. By their very existence and narrative power, they said something more—namely, that even such an evil, although mightily armed, was not omnipotent! They gave us, quite obviously, a lease on life. This was more astounding than anything—one man versus virtually all of the regime’s vast machinery of lies, stupidity, brutality, and ability to cover up evidence. This was a conflict waged by a solitary fighter such as comes along once in a millennium. And in every sentence, the victor’s identity came through unmistakably. But unlike the victories won by the regime, this one had nothing bombastic about it. I call it an Easter victory, one that passes through the medium of death to resurrection. In the Archipelago narrative, people rose from the dead, transformed in the dust of the camps, the country rose from the dead, the truth rose from the dead… It was the resurrection of truth in man and the truth about man out of the complete impossibility that this could happen”.

The most talented contemporaries of Solzhenitsyn, having been captivated by him as a writer, did not conceal their shock when they made the acquaintance of Solzhenitsyn the man. It seems the first to discern Solzhenitsyn’s magnanimity was the Russian poet and Nobel prize winner Anna Akhmatova. She said about him: “A bearer of light!… We had forgotten that such people exist… A surprising individual… A great man.”

Solzhenitsyn was a servant of humanity: by the example of his life he restored in many people a sense of personal dignity and a sense of hope. Solzhenitsyn not only informed the world about the reality and scope of evil, he also inspired people to greatness and changed the lives of many.

Solzhenitsyn’s reputation was high at home and abroad as long as he limited himself to criticizing Stalin, as in such early works as One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. This suited the purposes of the Soviet leader Khrushchev, who was conducting a campaign against Stalin’s personality cult. It also suited many Western intellectuals, who admired the October Revolution but felt that Stalin had betrayed it. In subsequent works, Solzhenitsyn made it clear that he opposed not only Stalin, but Lenin and the October Revolution. He even rejected the February Revolution. And he did not hesitate to write an open letter to the Soviet leadership setting forth his heterodox views. Thus, he earned the undying enmity not only of the Soviet regime, but also of the legions of Western intellectuals—many his erstwhile supporters—who were broadly sympathetic to the revolutionary cause and its secularizing aims. Once disgorged into Western exile, he faced incomprehension and derision for his failure to pay obeisance to secular materialism. His growing army of detractors, unable to allow the legitimacy of a worldview that contradicted their own, soon made him out to be an enemy of all freedom and progress. Solzhenitsyn remained utterly unfazed.