Presentation of Alex Havard at the University of Mary (Bismarck, North Dakota)

Watch the video of the presentation of Alex Havard at the University of Mary (Bismarck, North Dakota).

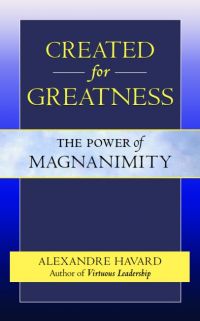

Review of Alexandre Havard’s “Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity”

A valuable contemporary philosophical book to help understand why abandoning virtuous achievement is a serious anthropological mistake.

Link to original. Author – Michael Severance

By the end of January, most of us have given up on our New Year’s resolutions. These are goals we enthusiastically set during the silent nights of self-reflection that Christmas affords us. We contemplate our Savior’s magnificent and humble life in contrast with our own feeble and self-seeking, sinful existence. We intensely desire personal renewal to become holier and nobler persons; yet, alas, we lack the will to actualize our true human potential.

Many blame the failure to commit on laziness or some other insuperable vice; others point to the natural distraction a busy life has on our focus once we are caught up in the flurry of school and work again.

While true for the most part, such excuses are symptomatic of a deeper mea culpa based on a lack of anthropological clarity of what human beings are meant to be.

Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity (Scepter, 2014) by the French-Russian author Alexandre Havard provides a remedy to this intellectual and spiritual gap. It is one of the most valuable contemporary philosophical books to help us understand just why abandoning virtuous achievement is a serious anthropological mistake, leading to general discontent and even despair.

Havard’s short book—just 96 pages—is essentially the sequel to his acclaimed, multi-language publication Virtuous Leadership: An Agenda for Personal Excellence (Scepter, 2007). In it the Moscow-based executive leadership coach dedicates five chapters, replete with practical and spiritual wisdom, to the virtue of magnanimity — what he calls the “jet fuel…, the propulsive virtue par excellence” of human achievement.

Upon reading Havard’s book I could not help but reflect on Alasdair MacIntyre’s 1981 masterpiece After Virtue. I was reminded of his criticism of a post-modern civil society that is bedeviled by its lack of belief in a true, objective model of mankind and moral behavior — one rooted in dignity, rationality, and virtuous agency. The self-less, heroic and virtuous living that once propelled so many great generations before ours to the heights of human exploration, invention and even sainthood, now plays second fiddle to rules and useful principles.

What guides human action nowadays, as a result, is whatever proves personally useful or pleasurable to any one particular person at any given time.

Yet, as Havard argues in his book, once we embrace hedonism and utilitarianism, we not only become small-minded, we also become feeble and ultimately fearful while mistakenly believing we are incapable of great things. Our pusillanimity when combined with fear, he writes, “engenders despair, and despair paralyzes the soul…Despair is a vice,…because it condemns man to mediocrity and decline.”

As another example of what deadens the magnanimous soul, Havard also faults the egalitarianism praised by communist and socialist societies. “[It] destroys in man his very sense of greatness…In their dignity, human beings are radically equal, but in their talents, they are radically unequal.”

During his business leadership seminars, he notes, Havard has seen a more than a few examples of strong-willed, self-centered persons –übermenschen which would make Nietzsche proud. He, therefore, wisely unpacks the natural virtue of magnanimity in perfect harmony with the religious virtue of humility, writing that they are “sine qua nonof personal fulfillment” and “inextricably linked”.

“Magnanimity and humility go hand in hand. In specifically human endeavors, man has the right and duty to trust in himself (this is magnanimity), without losing sight of the fact that the human capacities on which he relies come from God (this is humility). The magnanimous impulse to embark on great endeavors should always be joined to the detachment that stems from humility, which allows one to perceive God in all things. Man’s exaltation must always be accompanied by abasement before God.”

“Magnanimity without humility is [therefore] no magnanimity at all. It is self-betrayal and can easily lead to personal calamities of one kind or another,” the author warns us.

Throughout the book Havard remains a sensible realist. His writing – an advisory style – is terse, practical-orientated, and void of hyperbole. He adequately explains that, while difficult, it is certainly possible to become magnanimous if we are ready to incorporate the many other sustaining virtues involved. In his introduction and later chapters, he provides a helpful review of and exercises on the four cardinal virtues – prudence, temperance, courage and justice. He successfully ties in aretology (the study of virtues and their interrelation) into the larger picture of a magnanimous life and its various specific challenges.In addition, he convincingly explains how the theological virtues of faith, hope and charity are necessary to perfect all the good habits we learn and acquire by nature.

Finally, it must be pointed out that Havard’s book does not lack in real-life anecdotes of heroic virtue and leadership. In Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity, every page is peppered with inspiring examples of how renowned leaders have lived up to their full human potential and whose lives were simultaneous testimonies to both greatness and humility.

Highlights include wide-ranging stories about actors, singers, CEOs like Francois Michelin and Darwin Smith, St. Joan of Arc, World War II legend General Charles de Gaulle, Abraham Lincoln, Olympian Eric Liddell, and the founders of the European Union. Intertwined in the numerous historical references are thought-provoking quotes from Russian novelists, poets, and European intellectuals.

Ultimately for this devout Catholic author, it is Christ to whom he gives the fullest attention as the ideal of a perfectly magnanimous life. “If I had not spoken of Christ and Christianity,” Havard writes in the postscript, “I would have been guilty of intellectual dishonesty, ingratitude, and impiety.”

January 2015 letter

Dear friends of HVLI,

I hope that you are doing well. Following are the HVLI developments since my June 2014 letter.

I must begin with some very painful news: Bill Christensen, who was instrumental in the beginnings of HVLI in the US, passed away on December 16. Bill had been a direct response creative consultant for over 25 years and his contribution to the growth of Virtuous Leadership in the US was extraordinary. He was a musician and song writer, as well as a poet and creative writer. Bill was a prayerful man, deeply devoted to his faith and his family, with a gift for friendship. Please join me in praying for his soul.

I must begin with some very painful news: Bill Christensen, who was instrumental in the beginnings of HVLI in the US, passed away on December 16. Bill had been a direct response creative consultant for over 25 years and his contribution to the growth of Virtuous Leadership in the US was extraordinary. He was a musician and song writer, as well as a poet and creative writer. Bill was a prayerful man, deeply devoted to his faith and his family, with a gift for friendship. Please join me in praying for his soul.

Please note that we have redesigned our website: www.hvli.org. I hope you like it and find it useful. It is the work of Stanislav Volkov, a student of the Moscow Bauman Institute. Your feedback on the site is appreciated and will help us improve it.

On November 14th I presented at the “Winning the Hearts” people management ReForum in Moscow to some 600 businessmen. This extremely important event took place at the Skolkovo Business School in Moscow. It was a powerful occasion to spread Virtuous Leadership ideas all over Russia.

An additional approach that we’ve used since June 2014 has been the organization of regularly scheduled Virtuous Leadership sessions for small groups of 10 to 20 University students. Some 70 Russian students have received Virtuous Leadership education using this method in 2014.

Monthly we invite a virtuous leader guest to talk to the students about his life experience. This very popular program has proven to be very effective.

Monthly we invite a virtuous leader guest to talk to the students about his life experience. This very popular program has proven to be very effective.

In November I had the opportunity to present at the Kazakh Economic University (Almaty, Kazakhstan), the Bauman Moscow State Technical University and the First Moscow State Medical University. The universal appeal of the Virtuous Leadership approach to living continually draws people with very different backgrounds.

I am happy to announce that a second edition of «Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity» was published in October.

Created for Greatness explains the virtue of magnanimity, a virtue capable of setting the tone of your entire life, transforming it, giving it new meaning and leading to the flourishing of your personality. Magnanimity is the willingness to undertake great tasks; it is the source of human greatness. Along with humility, it is a virtue specific to true leaders emboldened by the desire to achieve greatness by bringing out the greatness in others. Complete with practical steps and points for personal examination, this book will not only inspire you, but will place you firmly on the path to a more magnanimous life.

I hope that your Christmas Season was a blessed one., and look forward to meeting many of you during my February 2015 trip to the US.

All best wishes for a happy and healthy 2015.

Do not hesitate to follow us everyday on Facebook or Twitter. You will find there useful material for contemplation and action. I prepared this material in 2014 and we began to publish it on January 20, 2015. This is Virtuous Leadership food for everyday.

Alexandre Havard

Virtuous Leadership at ReForum Winning The Hearts in Skolkovo

On November 14th Alexander Havard presented at the “Winning the Hearts” people management ReForum in Moscow.

Virtuous Leadership at I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University.

Nov 13, Virtuous Leadership meeting with students and professors of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University.

Virtuous Leadership on Kazakh Economic University (Almaty, Kazakhstan).

On Oct 24, Alexandre Havard presented at the Kazakh Economic University (Almaty, Kazakhstan).

Watch video:

First part http://youtu.be/hh6fmBqyww4

Second part http://youtu.be/TH2ZvuNql8k

Alexandre Havard on Great Leaders, Interview for TruthAtlas

Picture: Havard speaking to a business school audience in Moscow this year. Before stepping back on board, however, he heard a voice behind him. It was the old woman, and she was running toward him as fast as she could, a bouquet of flowers in her hand. With a huge smile, she offered them to him and left without saying a word. As Havard’s bus crossed the border into Finland, he reflected on what this old woman had done: Although destitute, she bought flowers with the money he’d given her, with no certainty she would even find him again. “She could have used the money to have a nice dinner,” writes Havard, “Instead, she bought me a gift, and because this was not from her surplus, made a gift of herself to me. I was overcome with joy, with a deep love for life, with a desire to convert, to purify my heart, to be better.” Havard, a native of Paris now based in Moscow, eventually went on to found the Havard Virtuous Leadership Institute. A lawyer by profession, he graduated from the Paris Descartes University, one of France’s leading law schools, and practiced law in several European countries. He now offers leadership seminars to senior business executives and university students around the world. In the United States, Havard has presented his leadership program to the U.S. Army War College, the Harvard Business School, and the Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC). His 2007 book “Virtuous Leadership” has been translated into 15 languages, and he is the author of the 2011 book “Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity.” Havard now has leadership centers in Moscow, Washington, Shanghai, Nairobi, and Bombay. I spoke to him about his passion to form leaders and help them achieve greatness:

Picture: Havard speaking to a business school audience in Moscow this year. Before stepping back on board, however, he heard a voice behind him. It was the old woman, and she was running toward him as fast as she could, a bouquet of flowers in her hand. With a huge smile, she offered them to him and left without saying a word. As Havard’s bus crossed the border into Finland, he reflected on what this old woman had done: Although destitute, she bought flowers with the money he’d given her, with no certainty she would even find him again. “She could have used the money to have a nice dinner,” writes Havard, “Instead, she bought me a gift, and because this was not from her surplus, made a gift of herself to me. I was overcome with joy, with a deep love for life, with a desire to convert, to purify my heart, to be better.” Havard, a native of Paris now based in Moscow, eventually went on to found the Havard Virtuous Leadership Institute. A lawyer by profession, he graduated from the Paris Descartes University, one of France’s leading law schools, and practiced law in several European countries. He now offers leadership seminars to senior business executives and university students around the world. In the United States, Havard has presented his leadership program to the U.S. Army War College, the Harvard Business School, and the Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC). His 2007 book “Virtuous Leadership” has been translated into 15 languages, and he is the author of the 2011 book “Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity.” Havard now has leadership centers in Moscow, Washington, Shanghai, Nairobi, and Bombay. I spoke to him about his passion to form leaders and help them achieve greatness:

ZOE SAINT-PAUL: You’ve written two books about virtue-based leadership. In a nutshell, what is it? HAVARD: Leadership is about greatness and service. Greatness is a result of being magnanimous and service is a result of being humble. Magnanimity and humility are the key virtues specific to leaders. Magnanimity is the thirst to lead a full and intense life, and humility is the thirst to love and sacrifice for others. This is what all leadership is fundamentally about.

What inspired you to leave your career as a lawyer in France and begin teaching and writing about leadership around the world?

Picture: Havard during an appearance in Kiev earlier this year (2013). I was lecturing university students on the history of European integration and spent hours helping them understand the hearts and minds of the European Union’s founding fathers. My students were amazed by their greatness, and I found the students’ enthusiasm infectious and uplifting. It led me to want to dedicate myself to forming leaders. If one day I quit teaching business executives, I will never quit teaching young people; one needs to inhale before exhaling; likewise, I need to witness hope before speaking about it.

Picture: Havard during an appearance in Kiev earlier this year (2013). I was lecturing university students on the history of European integration and spent hours helping them understand the hearts and minds of the European Union’s founding fathers. My students were amazed by their greatness, and I found the students’ enthusiasm infectious and uplifting. It led me to want to dedicate myself to forming leaders. If one day I quit teaching business executives, I will never quit teaching young people; one needs to inhale before exhaling; likewise, I need to witness hope before speaking about it.

I think many people assume that leaders are born, not made — you disagree. Why? Human personality is made up of temperament and character. Temperament is given to us by nature. Leaders have very different temperaments. Temperament is related to biology and genetics: We are born with it, and we cannot change it. Character is built on temperament and made up of virtues. The most fundamental virtues are prudence, courage, self-control, justice, magnanimity, and humility. Virtues are essentially spiritual qualities, and they’re acquired. We are not born with character; it’s something we build. The virtues that make up character give a leader power and the capacity to do what people expect. For instance, prudence allows a leader to make right decisions; courage, to stay the course and resist pressures of all kinds; self-control, to subordinate passions to the spirit and fulfill the mission at hand, and justice, to give every one his due. Because leadership powers stem from character, and character is something we build, I always say, “leaders are not born: they are trained.”

You use the word “magnanimity” a lot, but it’s not something we hear much today — can you say more about what it means? Magnanimity is the striving of the spirit towards great things. The Greek philosopher Aristotle was the first writer to elaborate on the concept. For him, a magnanimous person is one who considers him or herself worthy of great things. This awareness of one’s value is something we find in all great leaders. It’s not merely a question of proactively seeking to make things happen but about conquering yourself, mastering your autonomy and freedom. For Thomas Aquinas — the most important philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages — a magnanimous person is one who considers himself worthy of doing great things. Magnanimity begins with an awareness of our personal dignity. We are not vegetables. We are not chimpanzees. We are spiritual beings. We have a rational mind and a free will. We have a powerful heart. We can enjoy truth, goodness, and beauty. We can know God. Magnanimity is a true vision of self. Every one of us possesses absolute meaning and dignity and we cannot value ourselves too highly. Without an awareness of our dignity, and without affirmation of it, there is no magnanimity — and no leadership.

How does magnanimity relate to a leader’s vision and mission? And how does it change the way a person exercises leadership? Leaders always have a dream, which they invariably transform into a vision. A vision illuminates the mind and the heart and lifts the spirit. It can be communicated to others and, in fact, must become ashared vision. A leader can’t be the only one who knows where the enterprise is headed while the others follow blindly like sheep; the followers of a leader are partners in a noble enterprise. For the leader, a vision gives rise to a mission, which is translated into action. Many people have dreams and visions, but leaders have the unique ability to concretize them as missions. To identify a mission, you need to be aware of your talents. What are you good at? What are your strengths? There is only one way to find out: feedback analysis. You should explore many avenues and ask your friends or colleagues to help you discover this. Magnanimity is not just greatness of heart and mind, but action. It requires boldness and endurance. To carry out a mission you must work on your talents all the time. Although it is important to overcome your weaknesses, it is much more important to develop your strengths. For the true leader, action always stems from self-awareness. It is never mere activism, and never degenerates into workaholism. Leaders are always doers, but they never do things just for the sake of doing them; it is an extension of their being. The ultimate aim of magnanimity is personal excellence, and we must care more for people than for things. We must be fully aware that personal excellence—our own, and that of the people we lead— is a greater good than material success.

You speak of “greatness” as a key component of magnanimity. It is the same as being good or right? Not quite. Many people are satisfied with doing the right thing. Magnanimous people are not; they want to do the great thing. A great thing is always a right thing, but it’s more than that: It’s great. As soon as we understand the difference between what’s right and what’s wrong, we must try to understand the difference between what’s great and what’s small. Children can be educated in greatness. They can learn to do what is great, not just right. The great thing lifts our vision to higher sights, raises our performance to a higher standard, and builds our personality beyond its normal limitations. Magnanimity sets the tone of our entire life. Magnanimous people flee smallness. Many people do not change their ways when you tell them that what they do is wrong. But when you tell them that what they do is small, they often react. Some people are happy with being vicious, but few people are happy with being small.  Picture: Lecturing in Kiev in 2013.

Picture: Lecturing in Kiev in 2013.

You say that humility goes hand in hand with magnanimity in leadership, yet most probably wouldn’t associate many of today’s leaders with humility. Why is it so important? Humility is about two habits of being: living in the truth and serving others. To “live in the truth” is to recognize the greatness of God and your nothingness as a creature, as well as your natural weaknesses and personal faults. It is also to recognize your dignity and greatness, as well as your talents and virtues. Lastly, it is to recognize the dignity and greatness of others. Service is the natural consequence of living in the truth. It’s the summit of humility. Leaders serve by bringing out the greatness in others and helping them develop their own capacity to realize their human potential.

How does a leader bring out the greatness in others, exactly? By helping them discover their talents, develop a sense of their own worth, and a sense of freedom and responsibility. These are the 10 ways I suggest leaders do this:

- Pull rather than push; teach rather than order about; inspire rather than berate.

- Solicit their contributions in solving problems.

- Advise and encourage, but don’t interfere in their tasks without good reason.

- Delegate power.

- Challenge them.

- Practice collegiality in decision making.

- Deepen the commitment of team members to the shared mission.

- Promote your organization, rather than yourself.

- Don’t make yourself irreplaceable — share information.

- Identify, develop, and nurture future leaders.

How does a person grow in virtue? By practicing it. Virtue is a habit. First, we must train our hearts. In order to grow in virtue the first step is to value it. We need to contemplate the intrinsic beauty of virtue and desire it. The contemplation of virtue elevates us above ourselves and causes our soul to sprout wings. And virtue must be put into action – it is not enough to simply think about it.

What is the biggest challenge leaders face when it comes to being effective? False humility — a humility that excludes magnanimity.

Do you think leadership has changed over the years? Does effective leadership today require different abilities or approaches, or does it remain timeless? The leadership that interests me is not so much about style and methods. It’s a fundamental leadership based on character, such as it was perceived in antiquity. This kind of leadership will never change.

Who are some of the unsung hero-leaders of our time? What makes them heroic in your view? [Russian novelist] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and [French pediatrician and geneticist] Jérôme Lejeune. What stands out to me is their perseverance in the implementation of their magnanimous dreams.

Who are the leaders who’ve had the greatest impact on your life and work?  My parents. As part of our education, our parents took us to the theater to see “Crime and Punishment” and “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” They took us to the movies to see Andrei Tarkovsky’s “The Mirror.” They took us to Egypt and to New Orleans. They threw us into the water at the age of 3 and taught us to swim against the current. They taught us to sail on the high seas and not be afraid. We sailed through storms on the Atlantic. I have learned more at sea than anywhere else. Our parents were special: They taught us to do what others usually do not do.

My parents. As part of our education, our parents took us to the theater to see “Crime and Punishment” and “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” They took us to the movies to see Andrei Tarkovsky’s “The Mirror.” They took us to Egypt and to New Orleans. They threw us into the water at the age of 3 and taught us to swim against the current. They taught us to sail on the high seas and not be afraid. We sailed through storms on the Atlantic. I have learned more at sea than anywhere else. Our parents were special: They taught us to do what others usually do not do.

Who truly inspires you — and if you could ask him or her one question, what would it be? Josemaría Escrivá, a Catholic saint. His biographer says the most important human virtue of Escriva was magnanimity. My question to Escrivá would be: How do you stay in close touch with the little things that make up reality?

If you could give one piece of advice to young people today, what would it be? I would tell them this: Seek the company of magnificent people who are conscious of their dignity and manifest it in the way they live. These magnificent people can be your parents, your friends, the people you meet or hear about as you go through life. Contemplate them, study them, seek to imitate them. To grow in magnanimity, you need to create around yourself a magnanimous environment. Leaders have a plan for building up their personalities and those of their followers. They know that in devising such a plan they must be selective. Leaders do not read just any books or magazines, watch just any films, or listen to just any music. Aware of their own dignity as human beings, they fill their hearts and minds with that which is noble.

Virtuous Leadership in Continental Chinese (Beiging)

The Chinese Continental edition of Virtuous Leadership, published by the Social Sciences Academic Press, the publishing wing of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, is now available. Click here.